This Colombian monk set up residence in a mountain sanctuary 17 years ago in the Middle East.

BY ABBY SEWELL

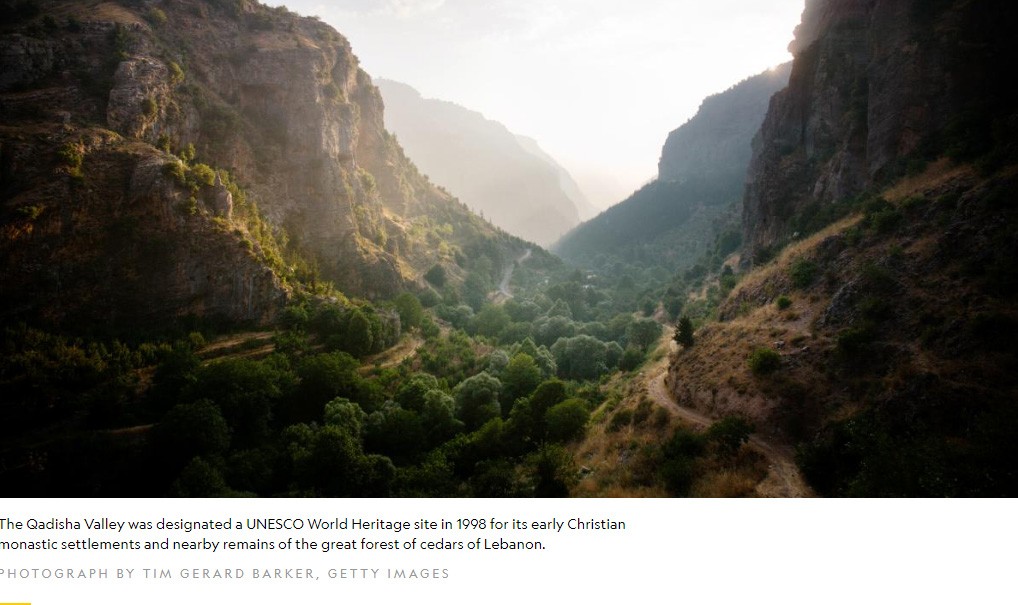

On the sun-dappled terrace of a centuries-old chapel chiseled into a cliffside overlooking Lebanon’s Qadisha Valley, the hermit was lecturing one of his daily visitors on his choice of body art.

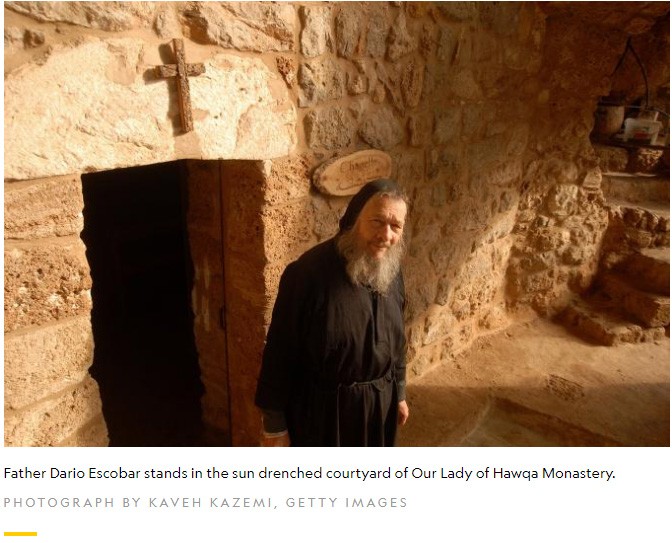

Father Dario Escobar, an 83-year-old Maronite monk from Colombia, has become something of a niche tourist attraction since he set up residence in the mountainside enclave 17 years ago. On this hot mid-September day, three hikers from Beirut arrived late in the afternoon hoping to catch a glimpse of him. Initially, it seemed that they would be disappointed, as Escobar was hidden away in his chambers.

But some 20 minutes later, the hermit emerged to close the heavy wooden gate leading into his compound for the night. He paused to chat with his visitors in a mix of English, Arabic, and French.

“They’re very beautiful, but they’re mamnoua,” or forbidden, Escobar said with a laugh. He was referring to the ornate rose tattoo and woman’s face that were inked across Ronnie Shalhoub’s biceps, a fitness instructor from Beirut. “Is that your mother?” Escobar continued. Shalhoub confirmed that it was. “But how? Your mama is beautiful—you are ugly!”

Escobar—who insists he is not related to his countryman, the notorious drug lord Pablo Escobar (although he said the common name once got him detained for three hours in the Detroit airport)–came to Lebanon 27 years ago. He heard about the Qadisha Valley’s natural beauty and monastic history from a Lebanese priest he met in Miami after joining the Maronite Church, a branch of the Catholic Church with its base in Lebanon.

“I came because only in Lebanon there are hermits,” Escobar said.

The Qadisha Valley, or holy valley in Syriac, dotted with monasteries and hermitages, has long been a refuge for Christians seeking solitude and safety.

Because the valley is difficult to access and removed from political centers, “it is attractive for people who want to live away from trouble,” says Anis Chaaya, an archeologist and Lebanese University professor who was part of the team that succeeded in getting the valley designated a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1998. “You had bandits hiding in this area and you had religious people who didn’t want to be persecuted.”

Escobar had to wait 10 years after arriving in Lebanon to receive the blessing of superiors at the Monastery of Saint Anthony of Qozhaya to take up a hermit’s life at Saydet Hawqa, or Our Lady of Hawqa Monastery.

The cliffside sanctuary was built in the late 13th century, following an invasion of the Qadisha Valley by the Mamluk army. Villagers had taken refuge in a cave near the site where the chapel is today, Chaaya says, but were sold out by a local man named Ibn Sabha, who suggested to the invaders that they could divert a nearby water source to flood the besieged villagers out.

Ibn Sabha “felt a problem with his conscience several years later on,” Chaaya says, and decided to ease the burden by financing construction of a church, which is now Saydet Hawqa.

In the hermitage’s small stone chapel, visitors light candles and leave prayers on scraps of paper under the altar. Outside, a courtyard overlooks the rugged valley below.

Escobar’s quarters include an office where he has hand tools, a desk, a basket filled with small vials of holy oil to dispense to guests, and a shelf full of religious and linguistic texts with a human skull perched disconcertingly on top. Below, he has a small sleeping chamber with an ascetic’s bed–a thin foam pad covered by a board, with a stone as a pillow.

The hermit says his daily routine requires 14 hours of prayer, three hours of work, two hours of study, and five hours of sleep, and he adheres to a vegetarian diet.

“I eat only from my garden–potatoes, beans, everything,” Escobar says. An assertion that was somewhat contradicted soon thereafter when a group of women from the nearby town of Bcharre arrived to bring him a sack of provisions, including a bag of potato chips.

In the winter, the sanctuary might get no visitors in the course of a day. In the summer, hundreds, the hermit says. Some descend from the village of Hawqa, a 20-minute trek via a steep set of stone stairs. Others hike up from longer routes traversing the valley.

The visitors have come in increasing numbers since the creation of the Lebanon Mountain Trail in 2007, a 290-mile (470-kilometer) trail spanning the country from north to south. The trail does not pass directly by Escobar’s hermitage, but hikers often take the 45-minute detour to ascend to the chapel in hopes of meeting him, including during annual through-hikes organized by the Lebanon Mountain Trail Association.

Martine Btaich, president of the association, said Escobar’s enclave is one of many sites that has gotten more exposure since the trail was completed. The growing culture of hiking and ecotourism among the Lebanese, she says, has provided a buffer against the fluctuations of foreign tourism.

“Lebanese are more interested in getting to know their country now,” she says, “and I think it’s a resilience card against all the turmoil in the region.”

Some of Escobar’s visitors come to ask for his blessing for newborn babies or engagements—or, in one case, for a man in a wheelchair who was carried to the chapel by four people. Others are simply curious to meet the unusual hermit.

Georges Zgheib, a tour guide who has been working in the Qadisha Valley since 2006, said he often brings groups to the chapel, although whether they meet the hermit or not is a matter of luck.

“It’s up to his mood,” Zgheib said. “Sometimes if he’s out, he barely speaks to people. Sometimes he laughs and tells jokes, and people laugh with him.”

The hermit is particularly known for his tendency to make lecherous jokes to attractive female visitors. “You stay here and I’m going to buy a pillow, a good pillow,” he told one of them, as he showed the guests his sleeping quarters.

A younger, Lebanese monk, also lives in the valley, Zgheib said, but he is more traditional in his ways than Escobar.

“That one, he doesn’t speak to people,” Zgheib says. “Never.”

A third hermit grew too elderly and infirm for the solitary life and was taken in at the monastery of St. Anthony. Escobar said that will eventually be his fate as well.

“I want to stay here for good, but if I am a very old man, the superiors take them then to the convent,” he says.

But for now, the devout and the curious can still find the unusual hermit of the Qadisha Valley in his mountain sanctuary.

Abby Sewell is a freelance journalist based in Beirut covering politics, travel, and culture. Follow her on Twitter at @sewella.

Article Source: [National Geographic]

You must be logged in to post a comment.